Through faith, we understand that the worlds were framed by the Word of God, so that things which are seen were not made of things which do appear.

Hebrews 11, The Holy Bible

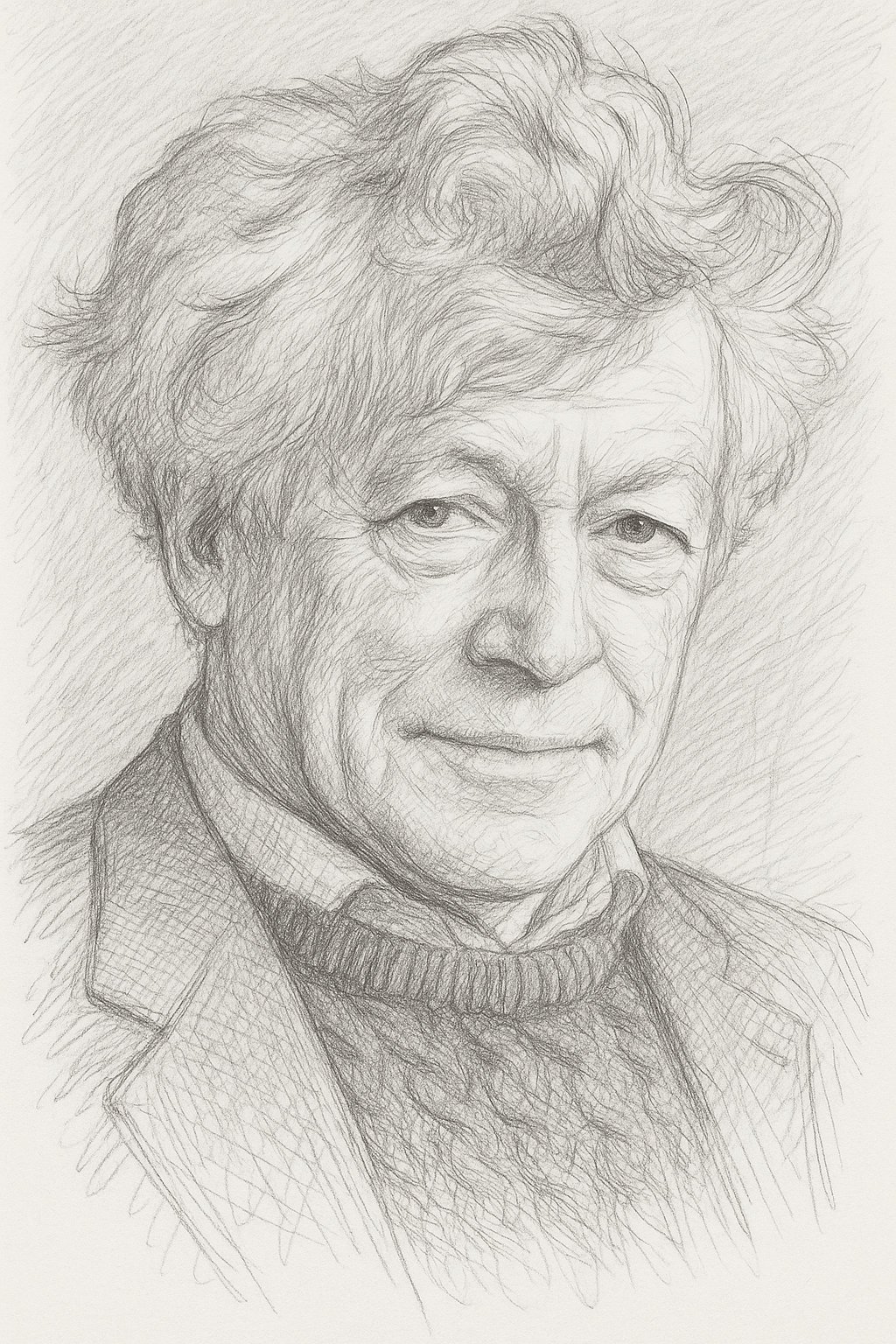

As an artist of Christian faith, my chief instruction and influence have always come from the Holy Bible and the glorious testimony of Jesus Christ, who has brought me to the love of the Truth in all things. Over the course of the years, various Christian ministers, writers, artists and thinkers have also duly made their mark on my thinking, and hence my way of approaching art and culture. One particularly gifted thinker whose writings have often articulated some of my own thoughts and intuitions is Sir Roger Scruton.

In a cultural stage groaning under the strain of moral disorientation, cultural marxism, and political self-parade, Roger Scruton (1944–2020) stood as a lonely but luminous voice in defence of Beauty — not as luxury, not as ornament, but as Truth made visible. To Scruton, beauty was not peripheral to life, but essential to our moral and spiritual flourishing. And nowhere was this more evident than in art. Today, the world often reduces art to provocation or activism, but Scruton insisted that great art had far more meaning and depth, revealing the truth about the human condition and its relation to form, order, and grace.

Beauty as One of the Forms of Knowledge

Scruton argued that aesthetic experience can be a mode of knowing, distinct from scientific or utilitarian knowledge. While science explains, and technology controls, art discloses. When we encounter a beautiful painting, hear a moving sonata, or stand before a cathedral, we are not just stimulated; we are shown something — about ourselves, about our longings, about the world as it might be when touched by the light of meaning.

For Scruton, beauty had an almost sacramental character — it mediated the invisible. The artist, then, was not a self-expressing rebel, but a kind of spiritual craftsman: one who gives form to what is inwardly known but outwardly difficult to say. Scruton’s writings return often to the idea that great art hints at something beyond itself. Even when not explicitly religious, art at its best carries within it a longing for transcendence. Thus he admired the work of painters such as Poussin, Turner, and Friedrich — their compositions are not abstract escapes, nor realistic imitations, but meditations: carefully composed invitations to contemplation. They give us beauty with depth, not surface charm.

Such beauty, for Scruton, does not distract us from Truth but leads us toward it. In art, we see not merely what is, but what is worthy of being seen.

Finally, brothers, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is commendable, if there is any excellence, if there is anything worthy of praise, think upon these things.

Philippians 4, The Holy Bible

Form and Moral Imagination against Nihilism

Scruton was also a fierce defender of form and discipline in art. He saw modern culture’s rejection of form — in favor of spontaneity, shock, or political gesture — as a betrayal of art’s very purpose.

To create beauty, he believed, was to engage in a moral act: to take raw material and impose upon it not arbitrary structure, but meaningful order. This is why the traditional painter, composer, or architect was so admirable to him — they practiced a kind of ethical restraint, shaping chaos into harmony.

The artist’s task, then, was not merely to express emotion but to refine it — to render it intelligible and shareable through form. In this, he echoed an older, classical ideal: that art should elevate the soul, not mutilate it. One of Scruton’s most penetrating insights was that much of contemporary art — especially in its institutional or avant-garde forms — had turned from beauty to ugliness on principle. It was no longer about revealing truth or reconciling us to reality, but about negating meaning, shocking the viewer, or venting despair. He saw this as a symptom of spiritual illness. For Scruton, the answer was not censorship or nostalgia, but love — love of the world, love of the human face, love of what is fragile and needs preserving. The real task of art is not to destroy meaning, but to recover it, and express it.

Beauty: Not Escape, But Homecoming

For Scruton, beauty was not a retreat from reality but a return to it, rightly seen. In the presence of great art — whether a portrait, a poem, or a pastoral landscape — we are reminded that life is not a random series of events, but a drama capable of order, grace, and hope.

In defending beauty, Scruton was defending something more than aesthetics. He was defending the soul’s capacity for truth, for love, and for home.

He has made everything beautiful in its time. Also, he has put eternity into man’s heart

Ecclesiastes 3, The Holy Bible